I take a last look, tracing the wall with my eyes to where it vanishes into the distance. Visible on the horizon is a tall chimney that belongs to the Haramachi power station, not a nuclear power, but a coal processing plant. Huffing and puffing white vapor into the sky, the smoke proves it is running again. Having been severely damaged by the earthquake and tsunami, the plant was relaunched in spring 2013. I am thus reminded of the fact that the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant was not the only plant accident resulting from the massive natural impact of the earthquake and the Tsunami waves, which reached up to around 30m in some areas. As well as the Haramachi plant, several other thermal and nuclear power plants were damaged by the Tsunami.[1] However, the terrific outcome at the Fukushima Daiichi of a Maximum Credible Accident (MCA) was arguably the only man-made disaster resulting from the natural disaster, human error giving bearing the 3/11 disaster a radioactive triplet.

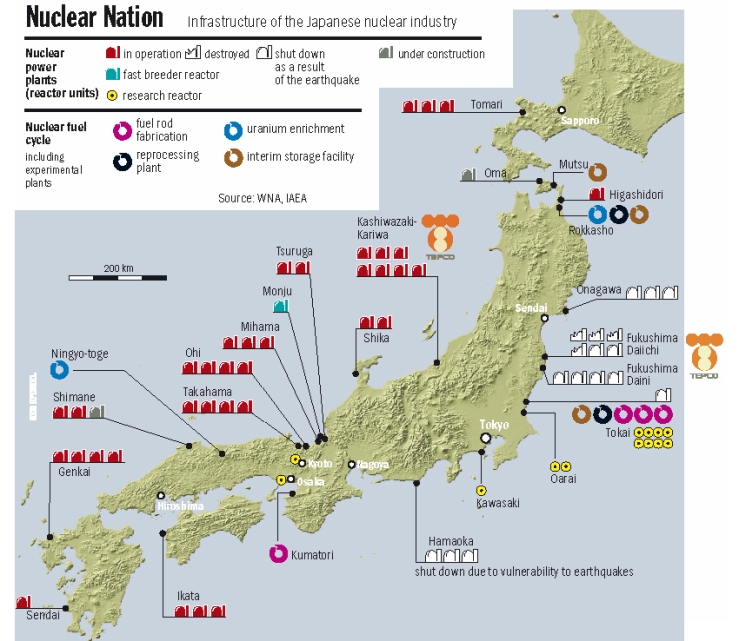

Along Tohoku’s eastern shoreline the prefectures of Fukushima, Miyagi, and Aomori have nuclear power plants (NPP) that were affected by the earthquake and Tsunami.[2] Aomori’s Higashidori NPP luckily was in maintenance shutdown when the disaster struck. However, the severe aftershocks that came about a month later on the 7th of April with a magnitude of 7.1 caused a power outage at the plant. Nevertheless, plant failure was avoided and the reserve system worked fine.[3]

After initial complete shutdown, as of the 10th of March 2016, only one of the 43 operable nuclear power plants of Japan, the Sendai plant is running again. However, under the guide of President Shinzō Abe’s pro-nuclear political agenda many more are awaiting their restart.[4] The recklessness of such an energy policy seems all the more apparent after the recent 7.0 magnitude earthquake in April 2016 in Japan’s southwest on the island of Kyushu. What irony to have the strongest earthquake since 3/11 strike so close to Japan’s only running plant. The feeling of discomfort caused by the alterity of this dystopian landscape doesn’t leave me when I get back in the car and we start driving again. We are still outside of the exclusion zone.

On our way closer to the Daiichi, we pass a couple of houses partly dismantled and severely damaged by the natural disasters. The bottom floor pulled away, standing like a stilt house, screen shields in flares, windows and panels removed, like someone took it and shook it violently, outside of the exclusion zone these houses are a rarity now. The areas outside of the strictest no-access zone are already cleaned meticulously. With their superimposed decontamination grid lines they have an almost sterile and orderly feel to them.

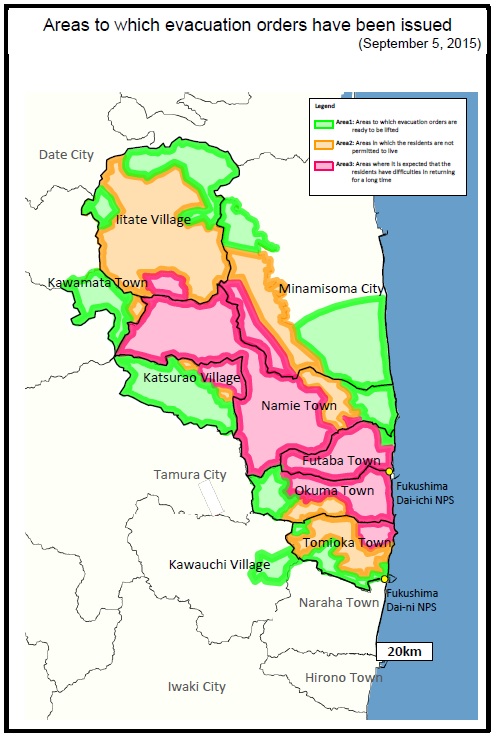

Throughout the last five years since the disaster, the demarcation lines, zones and checkpoints have been anything but rigidly fixed. The initial exclusion zone of the 20km evacuation radius around the Fukushima Daiichi power plant has been transformed into areas with different levels of access restrictions and security measures. Besides the strictest no-go exclusion or difficult-to-return zone closest to the power plant, there are those that can be accessed for short periods of time, as well as areas where evacuation orders are ready to be lifted. The zone at the core is off-limits to the public, special entrance permits are required to access it and even former residents are only allowed in for short periods of time around a dozen times per year. While you don’t need an official permission the second stage zone is accessible only during day time and any kind of business is prohibited. However, even these demarcations are continuously in flux, and we are surprised to see a checkpoint at a previously accessible road.

We revert to using a white lie and the guard grants us access. He notes down our number plate and we are free to pass into the restricted area. There are more carcass-like housing structures here, but I am surprised at how busy this area is, less than 6km from the power plant’s smoldering reactors. There are construction workers around. Former residents digging up their belongings from beneath the foundation walls of their houses that look like Roman ruins now. Even the Geiger counter confirms a radioactive contamination that is less than that measured in some parts of Tokyo. Governmentally inflicted borders are somewhat arbitrary and free to interpretation after all. Radiation doesn’t stick to a superimposed boundary and there hardly ever is a strict division between the here and there, the inside and the outside of the zone; except maybe for the linguistic labels that us humans stick to certain geographic terrains. Instead, the here and there of the Fukushima exclusion zone and the rest of Japan, or even the rest of the world, is metaphorical and hardly comprehensible at all. As I stand by the ocean, the chimney of the Fukushima Daiichi peeking out from behind some trees in front of me, I think about the impossibility of discerning where the fiction the nuclear catastrophe and its zone ends and where its reality begins. Radioactive contamination is elusive, and so are the ecologies it creates. I turn around: this is as close as I will get to the heart of the disaster, this time.

[1] https://www.tohoku-epco.co.jp/ir/report/annual_report/pdf/ar2012_p08p11.pdf‘

[2] There are no nuclear power plants located in Iwate.

[3] Besides the Higashidori NPP, Aomori is also the location of the Rokkasho Repossessing Plant, a nuclear waste dump, uranium enrichment and plutonium processing facility.

[4] http://www.nei.org/News-Media/News/Japan-Nuclear-Update

All images and content ©Theresa Deichert, 2016.